Ranked-Choice Voting and the 2021 New York City Mayoral Election's Democratic Primary: Review

In which it’s time for some game theory

This week, everyone is talking about ranked-choice voting, the electoral system implemented by New York City for its upcoming mayoral primary races. Many are confused about how to rank all the candidates and just want to go back to the old way, having the Police Benevolent Association President choose the hottest sexagenarian at the 432 Park Eyes Wide Shut party.

I, however, am not one of the confused. You see, in college I studied economics, a profoundly bizarre social science that teaches you little about the world and only slightly more about economics. Like any great discipline, economics is less interested in teaching you what to think than how to think: that is, like a sociopath. Anyway, the point is I took a class about social choice theory a long time ago and can walk you through it (with extensive help from Wikipedia).

What is Ranked-Choice Voting?

Ranked-Choice Voting (RCV), also called Instant-Runoff Voting (IRV), is an electoral system where instead of choosing only one candidate, voters are permitted to rank several in order of preference. Many variations exist, but for our purposes we are assuming a field of many candidates running for one position. In New York, you can list up to five mayoral candidates on your ballot.

Everyone’s first-choice candidate votes are tallied in an initial count. If someone wins the majority of the vote, they are the winner. If no one has taken a majority, then the candidate with the fewest number of votes is eliminated, and their votes are reapportioned to their voters’ respective second-choice candidates. The process of eliminating the worst-performing candidate and reapportioning their votes to the voters’ next-most preferred candidate (who is still in the race) continues until a candidate obtains a majority of the vote.

For the visually inclined:

Why Is This Good?

One of the main benefits of ranked-choice voting is its practicality. In many local elections where no candidate has a majority of the vote, states and municipalities spend significant time and money holding additional runoff elections with the top two candidates. With RCV, there is no need—the runoff is “instant.”

Ranked-choice also tends to provide results more in-line with the majority of voters’ preferences, at least when compared to a first-past-the-post (“whoever has the most votes wins”) plurality system. Plurality voting satisfies the straightforward ‘majority criterion,’ which states that if more than half the voters prefer one candidate over all the others, that candidate will win (“majority rules”). RCV satisfies this and the stricter ‘mutual majority criterion.’ This states that if more than half the voters prefer a group of candidates over all the others, the winner must come from that group.

More concretely, this reduces the potency of the marginal ‘spoiler’ candidate, who is unlikely to win, but siphons enough votes away from an ideologically similar candidate to make them both lose. Think Ralph Nader spoiling Al Gore’s presidential bid in 2000 (we can debate the extent to which he actually served as a spoiler another time). If we assume Nader and Gore voters preferred either over George W. Bush, ranked-choice voting would have led to a conclusive Gore victory: Nader would have been eliminated in an early voting round, and his votes would have been reallocated to Gore.

This generalizes further. With ranked-choice, a mutual majority coalition can support multiple candidates without fear of ‘vote-splitting’ handing the election to an undesired opposition candidate. There is no need to coalesce around one candidate, because RCV does that for you. For example, if the 2024 presidential election used RCV (pretend the Electoral College does not exist), the Democratic Party could simultaneously run Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Yours Truly without fear of Trump winning. As long as the vote totals for these candidates add up to over 50%, and these voters all agree any one of them is better than Trump, one of those candidates will eventually win. This occurs because each round of ballots would eliminate the worst-performing Democrat and funnel their votes to the others until only one remains, with the majority of the vote.

The second-order impacts of ranked-choice are less clear but worth consideration. Without a spoiler penalty, could RCV promote third-party support? Could it foster comity among the candidates, who now have to attract a broader base of support? In New York, Andrew Yang and Kathryn Garcia have campaigned together, and several interest groups have opted to support multiple candidates.

What’s the Catch?

There is no such thing as a flawless voting system. Many math proofs demonstrate that any electoral system can yield bad or contradictory results, most notably Arrow’s impossibility theorem. And while plurality voting’s shortcomings are more familiar, ranked-choice voting is perfectly capable of going haywire as well.

As a case study, let’s look at the 2009 mayoral election in Burlington, Vermont:

Progressive candidate Bob Kiss won the election after three rounds, beating out Democrat Andy Montroll and Republican Kurt Wright, who won the plurality vote on the initial pass. Looking at the tabulations, this appears to be an ideal outcome. The Republican candidate received a narrow plurality, but only because the majority vote was split between two left-of-center candidates. Later rounds rectified this and the Progressive candidate won.

However, in head-to-head matchups, Democrat Andy Montroll was favored by 56% of voters against Republican Kurt Wright, and by 54% of voters against Bob Kiss. He beat the other candidates even more handily (see below). So how did he lose?

When a candidate wins individual matchups against every other candidate, they are called the Condorcet winner. Unfortunately for Andy Montroll, ranked-choice voting violates the Condorcet criterion, meaning it does not necessarily choose the Condorcet winner as its election winner.

RCV also fails the monotonicity criterion, which states that a voter cannot improve a candidate’s chances of victory by ranking them lower on the ballot, and cannot harm a candidate’s chances of victory by ranking them higher on the ballot. This makes intuitive sense—voting for someone shouldn’t reduce the chances of them winning, right?

And yet, if you were an enterprising Republican living in Burlington, Vermont, in 2009, you would have had a prime opportunity to do just that. Most Kurt Wright voters preferred the more moderate Democrat Andy Montroll to the Progressive Bob Kiss. If just enough of them would have voted for Progressive Bob Kiss as their first-choice candidate instead of Kurt Wright, Wright’s support would have dropped enough to get him eliminated before Montroll or Kiss, and the bulk of the Wright votes would have then transferred to Montroll. The final round would have then become Montroll vs. Kiss, and, as mentioned earlier, Kiss would have lost the head-to-head matchup. So by voting for the Progressive candidate, a small bloc of strategic Republicans could have paradoxically…caused the Progressive to lose.

What Does This All Mean?

In ranked-choice elections, a mutual majority coalition can decide the winner for itself. Essentially, if a mutual majority coalition exists, the winner will be the candidate most-preferred within that bloc (the “majority of the majority”), rendering the votes of those outside the coalition irrelevant. This quirk occurs as a result of RCV satisfying the mutual majority criterion but failing the Condorcet criterion.

In the 2009 Burlington election, Kiss and Montroll had a combined 51.8% of the first round vote, and most of Montroll’s voters went to Kiss upon elimination, so we can understand Kiss-Montroll voters as a de facto mutual majority coalition. But even though most voters preferred Montroll over Kiss head-to-head, Kiss won, because within this left-leaning majority coalition, Kiss was favored over the more moderate Montroll. Wright supporters and the rest of the minority bloc’s preferences were ignored.

The 2009 Burlington election is not an outlier in this regard, either. RCV naturally encourages victories by left- or right-wing candidates even when most voters would prefer a moderate choice, so long as an ideologically-aligned bloc has a majority. Take a look at Alaska’s upcoming 2022 Senate election:

Here, Lisa Murkowski serves as the relatively moderate Republican whom liberal voters would likely prefer over Kelly Tshibaka. But since Murkowski and Tshibaka add up to a majority (AIP also leans libertarian/conservative), they can roughly form a mutual majority coalition, and the right-wing Tshibaka would win.

Since votes for candidates outside the mutual majority coalition are ignored in these cases, ranked-choice encourages these voters to vote tactically (i.e., differently than their true preferences to prevent an undesirable outcome). For instance, Burlington’s Wright voters would have been better off voting for Montroll over Wright, and Alaska’s Gross voters may need to support Murkowski to prevent an even less desirable candidate from winning.

Okay. What About New York City’s Mayoral Democratic Primary?

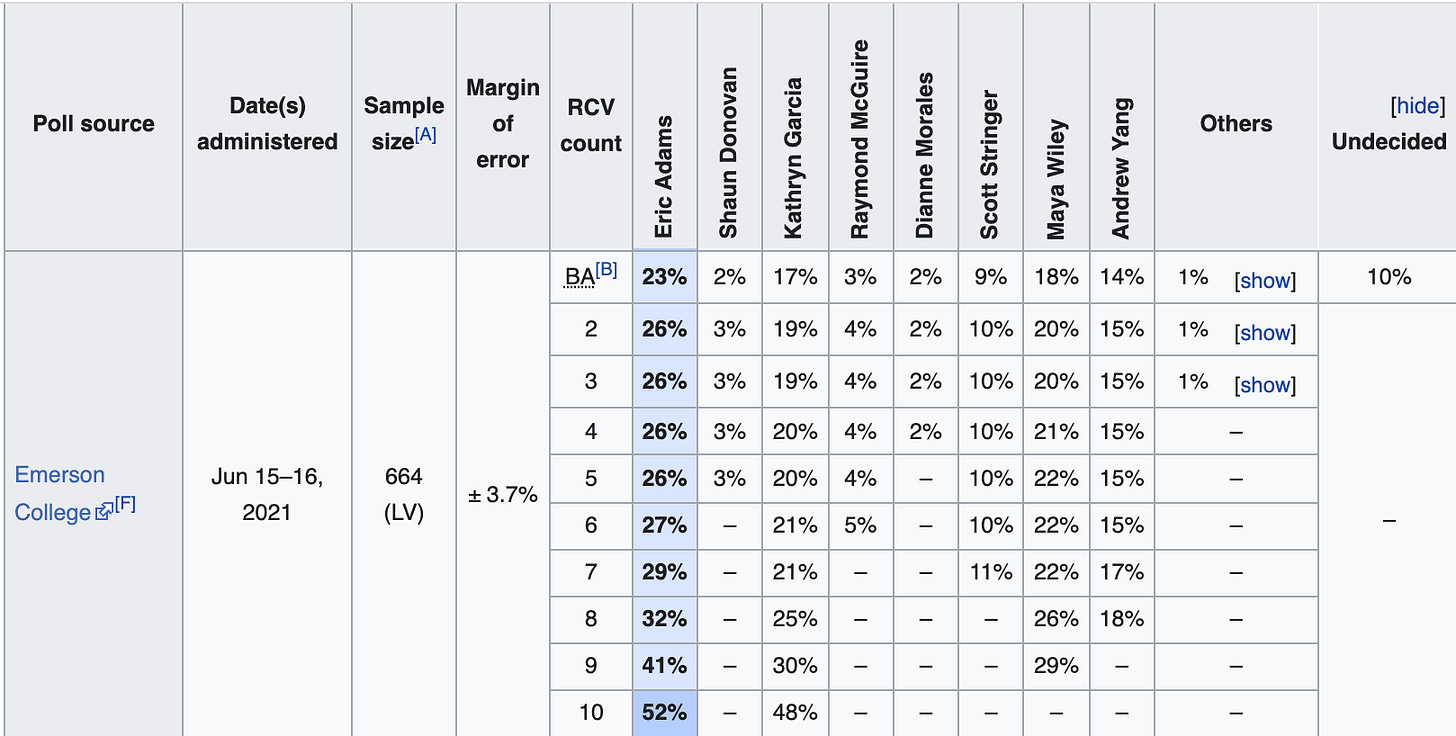

As someone who generally supports leftist candidates, I was intrigued by the possibility of a progressive mutual majority coalition icing out the moderates and selecting a left-wing candidate. Unfortunately, that is not even close to happening. Here are some recent ranked-choice polls:

To the extent that a ‘progressive’ coalition exists—Garcia-Morales-Stringer-Wiley?—it doesn’t add up to a majority, and it isn’t mutual—most of those voters don’t prefer these candidates over all others. Only Dianna Morales voters uniformly funnel toward Maya Wiley; others in the bloc are just as likely to head toward Eric Adams and Andrew Yang.

Adams remains the favorite, but Kathryn Garcia is making a late push and appears to be the strongest upset candidate, with Wiley close behind. Most Wiley voters funnel toward Garcia upon Wiley’s elimination, giving her a winning majority in some polls; however, Garcia voters don’t appear to reciprocate, which limits Wiley’s path to victory.

Meanwhile, Garcia has also been actively campaigning with Yang. This could be a huge boon for her, since Yang voters appear to prefer Adams as their second choice. Yang, once the favorite, appears to be trending downward in fourth place. If Yang’s effusive endorsement steers voters away from Adams and toward Garcia, the race could tighten even more. (Hilariously, Garcia has not endorsed Yang as her second choice.) It may be working—Adams has already decried their events as “voter suppression.”

A lot is still up in the air. Many polling outcomes fall within the margin of error, and the percent of undecided voters remains high.

What Should I Do?

Like many, I think Adams and Yang are the devil you know and the devil you don’t, respectively, and should be avoided at all costs. I personally find Wiley to be the best candidate who could plausibly win, and Garcia seems to have the best shot this side of Adams. So, my recommendation is simple: put Wiley and Garcia somewhere on your ballot, and don’t put Adams or Yang anywhere. Otherwise, vote for the candidates you like, and don’t vote for the ones you don’t like.

P.S.: Tactically-speaking, if you would like to support a candidate with no shot at winning, you should rank them high on your ballot so your vote actually goes to them. RCV allows you to do this without ‘throwing your vote away,’ since your vote will inevitably transfer to your second choice. But if you rank Wiley ahead of Paperboy Love Prince, for example, Prince will never get that vote—they will have been long gone by the time Wiley would get eliminated. Also, while you don’t have to list five candidates, there is no benefit to listing fewer, particularly if you have five candidates you would like to support. (There is no mutual majority coalition mucking things up in this race…I think.)

Happy Voting!

Sources

I find hyperlinks in articles distracting, so I’ve included sources for relevant images and information below. Let me tell you, dear reader, it’s mostly Wikipedia anyway.

Ranked Choice: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant-runoff_voting

Mutual Majority Criterion: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mutual_majority_criterion

2009 Burlington Mayoral Election: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2009_Burlington_mayoral_election

Condorcet Winner Criterion: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Condorcet_winner_criterion

2021 NYC Mayoral Election: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_New_York_City_mayoral_election

2022 Alaska Senate Election: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_United_States_Senate_election_in_Alaska#Primary_election

Eric Adams Complaining: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2021/06/21/nyregion/nyc-primary-election

Another Interesting Mayoral Race Poll: https://fairvote.app.box.com/s/uwqzhjcmu6pvjuz5qve33ioff0u7zndp